May 24, 2023

One of the most controversial topics surrounding the management of diabetic retinopathy revolves around when patients should be treated. Should we follow the traditional path of waiting until patients develop proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), or is it better to intervene earlier? This question has been debated among retinal specialists since the release of the pivotal PANORAMA study in 2020.

The PANORAMA study was a prospective randomized clinical trial in patients with moderately severe to severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) (Level 47 to 53) without macular edema who were randomly assigned to two different treatment schedules of aflibercept 2 mg vs. a sham injection.

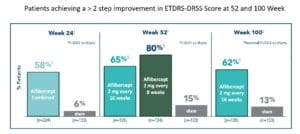

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients who had a ≥2 step regression on the ETDRS-DRSS grading scale from baseline at week 24, and at week 52. Secondary endpoints included the proportion of patients developing PDR or anterior segment neovascularization (ASNV), development of center involved diabetic mac edema (CI-DME) through week 52. All endpoints at week 100 were prespecified exploratory endpoints.

At week 52, two-thirds (65%) of patients receiving aflibercept 2 mg every 16 weeks and 80% of patients receiving aflibercept 2 mg every eight weeks achieved a ≥ 2-step improvement in ETDRS-DRSS score from baseline vs. 15% in the sham group. At week 100, 62% of patients receiving aflibercept every 16 weeks achieved a ≥ 2-step improvement from baseline vs 13% in the sham group. Moreover, the proportion of patients who progressed to PDR, ASNV, or CI-DME at 16 weeks and 52 weeks was significantly less than those who received the sham injection.

Sight Threatening Complications Much Higher in Sham Group

The development of PDR or ASNV at 52 weeks in eyes treated with aflibercept every 16 weeks or every eight weeks was 4% and 2% respectively, compared to 20% in the sham group. The sham group was also more likely to develop CI-DME (28%) compared to the aflibercept treated group (7% aflibercept q 16 weeks, 9% aflibercept every 16 weeks) at 52 weeks.

These results were sustained through the second year, when fewer patients with moderately severe to severe NPDR progressed to PDR, ASNV, or developed CI-DME. In patients who received a sham injection, 31% progressed to PDR or ASNV compared to 9% who received aflibercept 2 mg every 16 weeks. Center involved-DME occurred in 38% of the sham treated group compared to 11% of eyes treated with aflibercept 2 mg every 16 week1.

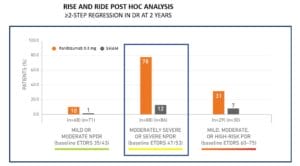

This 2-step regression was not unique to aflibercept. Indeed, treatment with ranibizumab showed similar diabetic retinopathy regression outcomes based on a retrospective analysis of 746 patients with diabetic retinopathy (levels 10-75) and DME that were randomized in the RIDE and RISE trials to receive ranibizumab 0.3 mg or sham injection. Like what was seen with aflibercept, 78% of patients with moderately severe to severe NPDR (level 47-53) receiving ranibizumab experienced a ≥ 2-step regression in DR at two years compared to 12% of patients receiving sham injection2.

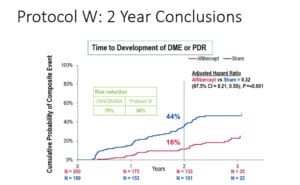

Finally, the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research (DRCR) Network did essentially the same prospective study as PANORAMA but specifically looked at visual acuity outcomes between the two groups as well as the risk of going on to develop visually threatening complications — CI-DME or PDR. Not surprising, the investigators showed that at two years, the rate of developing CI-DME or PDR was higher in the sham group compared to the aflibercept-treated eyes, 43.5% vs 16.3%. However, in looking at visual acuity between both groups, there was no difference in the outcomes.3 Delaying treatment until the development of PDR did not negatively affect the visual acuity outcome at two years.

So, clearly treatment of moderately severe to severe NPDR with anti-VEGF medications can result in a significant percentage of patients having a > 2-step regression in the level of diabetic retinopathy, and treatment seems to significantly reduce the risk of progressing to PDR or CI-DME. However, at two years, deferring treatment until the development of PDR does not seem to negatively impact the visual acuity outcome, which seems surprising given the risk of vision-threatening complications from PDR. Perhaps we need longer than two years to be able to accurately determine if there is a visual acuity benefit from earlier treatment. Four-year data is expected to be available within the next year.

Where Does This Leave Us?

The clinical trial data showing the ability to turn the clock back on diabetic retinopathy seems so powerful, yet most retinal specialists are still not treating patients who have (moderately severe to severe) NPDR. There are probably several reasons for this. First, the treatment is not benign. It requires frequent intravitreal injections, maybe even monthly initially, in patients that likely still have excellent visual acuity.

Remember, these are not patients with CI-DME who already have reduced visual acuity where the treatment protocols are well established. Not so in NPDR patients without DME. These are patients with good acuity that would have to “buy-in” to a treatment that requires frequent office visits as well as a significant treatment burden with a belief that the retinopathy will improve, and in the long term they will be better off. But for how long will patients need to be treated? Does the treatment go on indefinitely, or at some point can it be stopped? In PANORAMA even after two years, patients were still maintained on every 16-week injections.

Patients Often Tire of Ongoing Treatment

Treatment “burn-out” has become a significant issue in both AMD and the diabetic retinopathy populations where real-world outcomes are far worse than clinical trial outcomes as more and more patients get lost to follow up. No doubt this would become an even more significant issue in the NPDR population who could very quickly become disenchanted with needing to see their retinal specialist on an ongoing basis.

Finally, the DRCRnet perhaps provided the best reason for waiting to treat. If treating early does not result in a better visual acuity outcome, why would we put our patients through what potentially could be a rigorous treatment schedule when in the end treatment doesn’t result in better vision?

The final chapter, however, may still not be written. What if the DRCRnet four-year results show there is a visual acuity benefit by treating early? Does that become a pivot point for retinal specialist to adopt an early treatment protocol? That combined with more durable medications such as faricimab (Vabysmo) might reduce the treatment burden and put this back on the table.

In the meantime, the burden of diagnosing diabetic retinopathy still falls, in part, on the primary care optometrist and referring to the retinal specialist when appropriate. “When appropriate” can be different for each doctor depending on experience, comfort level, and mode of practice. Suffice it to say, I think it is better to get these patients to see a retinal specialist before they develop PDR regardless of whether they are going to treat them or not.

References

1 Wykoff CC. A phase 3, double-masked, randomized study of the efficacy and safety of aflibercept in patients with moderately severe to severe NPDR: week 100 results. Data presented at: Angiogenesis, Exudation, and Degeneration Annual Meeting; February 8, 2020; Miami, FL.

2 Wykoff CC, Eichenbaum DA, Roth DB, et al. Ranibizumab Induces Regression of Diabetic Retinopathy in Most Patients at High Risk of Progression to Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmology Retina. 2018;2(10):997-1009.

3 Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Josic K, et al. Effect of Intravitreous Anti–Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor vs Sham Treatment for Prevention of Vision-Threatening Complications of Diabetic Retinopathy: The Protocol W Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(7):701–712. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.0606.