August 29, 2023

Scleral lenses have made a resurgence in the specialty contact lens space over the last two decades. They have become an indispensable tool in eye care’s arsenal to manage refractive error in patients who don’t fare well with conventional methods. Sclerals were once reserved typically for vision rehabilitation and a means to avoid surgical intervention. Now, sclerals can be effectively fit on patients with regular and irregular astigmatism, dry eye, or even normal corneas that have failed other alternatives. With their increase in popularity came an increase in demand for high-performing optics. Patients who had been given their best distance vision in sclerals than they had ever experienced with any other lens modality want to be able to extend that clarity into their near world despite their presbyopia and without reading glasses.

Before multifocal optics were introduced into scleral lenses, the primary way to achieve adequate near vision without readers was monovision. Alternatively, aspheric optics can give a small near boost, but this is limited to early presbyopes. Monovision can work very well for some patients, but as we all know, the downsides of monovision include a loss of binocularity and depth perception as well as difficulty with patient adaptation. In comparison, patients prefer their vision in multifocal lenses over monovision for most activities.1 Thankfully, many scleral manufacturers offer multifocal optics in their lens designs.

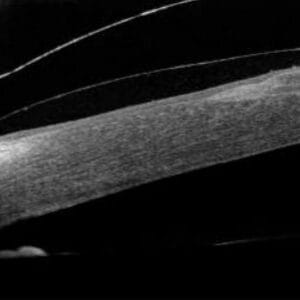

Minimal Lens Movement with Comfort and Stability

The benefits to scleral multifocals over alternatives include: vision stability for patients with dry eye who have fluctuating vision with soft lenses, improved comfort compared to small diameter rigid gas permeables, minimal lens movement that maintains proper optic zone alignment at all times, and the ability to fit highly irregular corneas.

Most scleral lens manufacturers offer a center-near multifocal design, but there are some center-distance designs available. The multifocal optics are applied to the front surface just like toric optics, so manufacturers cannot include both in the same lens design, which might be an issue for some patients. Multifocal designs work best in eyes with less than -1.00D of residual astigmatism. For patients with excessive residual astigmatism, modified monovision – where one eye is fit in a toric single-vision lens and the other a multifocal – might work well.

The principles of fitting multifocal sclerals are no different than fitting other multifocal options or standard sclerals. Patient selection and expectation management is key, which we have discussed in detail in our article, “Prepare Your Pre-Presbyope Patient for Multifocal Contact Lenses.” Determining least-minus/most-plus best corrected manifest refraction, eye dominance, HVID, and pupil size (in photopic and scotopic illumination) are necessary for proper lens design. Utilizing a fit set is also crucial to determining initial lens order and significantly cuts down on the amount of trial lens re-orders compared to empirical fitting. As such, many manufacturers do not offer empirical fitting.

When it Comes to Multifocal Sclerals, Less is More

We find that it is best to initially fit the patient into a distance-only lens until we have nailed down a proper fit and most-plus/least-minus distance prescription. Then we will order a new set of lenses with multifocal optics to be dispensed in-office. Surprisingly, once we finalize the fit with the distance-only optics, the amount of add the patient needs might be different from what we find on manifest refraction. We may not need to have as large an add in the multifocal optics as originally thought, or we may be able to utilize aspheric optics instead. A great rule of thumb with multifocals is “Less Is More.” Alternatively, you can order the initial lens with the multifocal optics included, but we find that increasing the amount of variables to simultaneously manage increases chair time and lens remakes.

Another benefit to sclerals is the ability to decenter the optic zone. The visual axis of the eye is more nasal and superior to the center of the cornea.2 Conversely, sclerals often decenter inferior-temporally due to the shape of the sclera, lens center-of-gravity, and superior lid forces.3 This can create issues with glare, halos, and ghosting with scleral multifocals. Topographers can be a useful tool to determine if the multifocal optics are not centered properly. Utilizing the tangential map, you can visualize the multifocal transition zone of a scleral lens on the eye and compare to the pupil location. Some scleral designs offer the ability to decenter the multifocal optics to better align with the visual axis and compensate for lens decentration. Alternatively, you can change optic zone size to alleviate this issue.

With the advances in scleral lens designs, practitioners have the ability to fit more patients in contacts than ever before. Many patients who have dropped out of contact lens wear due to dryness, unstable vision, discomfort, or any other reason that prevented them from wearing more conventional options can be re-fit into a scleral lens and still be able to achieve glasses-free vision at distance, intermediate, and near. Although adding another component to the scleral lens evaluation adds to the intricacies of the fit, the reward for both patient and practitioner are worth the added effort. Additionally, lab consultants are available and are an extremely valuable resource in maximizing success and reducing complexity in fitting multifocal scleral lenses.

References

1 Woods J, Woods C, Fonn D. Visual performance of a multifocal contact lens versus monovision in established presbyopes. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92(2):175-182

2 Artal, P. Optics of the eye and its impact on vision: a tutorial. Advances in Optics and Photonics, 2014;6:340–67

3 Vincent SJ, Alonso-Caneiro D, Collins MJ. The temporal dynamics of miniscleral contact lenses: central corneal clearance and centration. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2018;41(2):162-168.

Getty Images