April 26, 2023

Poor diet is the leading cause of mortality in the United States, causing more than half a million deaths per year.1 In a 2019 article in The New York Times, “Our Food Is Killing Too Many of Us,” Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition’s Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian and former secretary of agriculture Dan Glickman make the argument that improving American nutrition would make the biggest impact on our health care. The United States government is waking up to this knowledge. On May 27, 2020, the National Institutes of Health released its first ever strategic plan to accelerate nutrition research with the emphasis on the role of dietary patterns for optimal health. Americans are becoming sick and tired of being sick and tired. As a practitioner, there is not a day that goes by without a patient asking what lifestyle changes can help with their treatment.

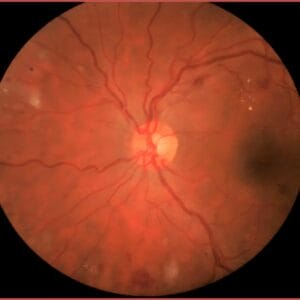

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) constituting most cases. Factors other than elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. Oxidative stress, axonal transport failure, neurotrophic factors, and nutritional factors have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) loss.2,3,4,5,6 There is a growing interest in non-pharmacologic and lifestyle changes in the management of eye disease.

Oxidative Stress

Glaucoma is a multi-faceted disease where many pathological mechanisms contributing to glaucomatous neurodegeneration are caused by, lead to, or contribute to oxidative stress, inflammation, reactive gliosis, and apoptosis.7,8,9,10 Of all external factors in our environment, diet is one of the largest influences on inflammation and oxidative stress. Low levels of ocular or systemic antioxidants are associated with POAG and more severe visual field loss.11,12,13 In clinical studies, a significant association between low serum levels of antioxidants, including vitamin C and D, and POAG have been reported.14,15

In a comprehensive review paper published in the European Journal of Ophthalmology in 2021,16 the authors conducted a literature review of the effect of dietary modification and antioxidant supplementation on intraocular pressure and open-angle glaucoma. They concluded that overall, experimental and animal studies thus far have shown promising results regarding the potential of antioxidants to control the oxidative environment in ocular hypertension and glaucoma. However, results from large population-based prospective cohorts and randomized clinical trials have shown mixed results. Based on the level of evidence thus far, the authors concluded that it is not yet possible to recommend a specific adjuvant treatment protocol.16 However, the following are evidence-based recommendations that have been shown to be beneficial adjuvants to standard glaucoma therapies.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids:

In multiple studies, feeding animals with omega-3 fatty acid-enriched diets over three to six months correlated with a reduction of IOP via improving aqueous outflow, the attenuation of stress response in retinal cells, and the prevention of retinal cell loss following IOP elevation.17,18,19,20 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2005-2008) data, a cross-sectional survey involving 3,865 participants from the United Sates, has shown that high dietary consumption of eicosapentaenoic acids (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acids (DHA) from omega-3s are correlated with a lower probability of glaucomatous optic neuropathy.16 Oral omega-3 supplementation for three months significantly reduced IOP in normotensive adults in a recent study, and this reduction is thought to be due to increasing aqueous outflow and anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3s.21 Omega-3s have neuroprotective effects and support ocular microcirculation.21

Vegetable and Fruit Intake:

Research has shown that a diet high in green leafy vegetables is inversely related to the risk of POAG.22 The protective effect is thought to be due to the abundance of nitrates in green leafy vegetables and the production of nitric oxide that is critical in the pathophysiology of POAG. Nitric oxide is a direct regulator of IOP, and it has been shown to be neuroprotective. It also regulates blood flow and vascular tone. Other foods that have been shown to increase nitric oxide are the flavonoids in dark chocolate, beets, garlic, pomegranate juice, citrus fruits, and watermelon.

MIND Diet:

The MIND diet is the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet that was developed as a strategy to promote healthy cognitive aging. It is a combination of the Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and it has been shown to reduce the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline.23 The MIND diet contains brain healthy foods such as green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, fish, poultry, olive oil, and moderate red wine. It limits red meat, butter and stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried/fast foods. The MIND diet has been shown to be neuroprotective in POAG independent of IOP-lowering effects.23

Coenzyme Q10:

Coenzyme Q10, also known as ubiquinone, is a vitamin-like compound found in every cell of the body. It plays a vital role in the production of energy within the mitochondria, which are the powerhouses of the cell. It also functions as an antioxidant and is neuroprotective. In glaucoma, coenzyme Q10 has been studied for neuroprotection and has been shown to reduce oxidative stress, improve mitochondrial function, and reduce inflammation.24, 25 It is important to note that roughly 60% of older Americans are on statin therapy to lower cholesterol and protect against heart attack and stroke. Statins have been shown though to reduce levels of coenzyme Q10 in the body by as much as 40%,26 so patients may want to incorporate coenzyme Q10 in their regimen. Good food sources of coenzyme Q10 include organ meats, fatty fish, soybeans, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. Coenzyme Q10 can also be taken in supplement form.

Ginkgo Biloba:

Ginkgo biloba is a plant native to China. The leaf contains about 20 different types of flavonoids and has been studied for neuroprotection in glaucoma. Ginkgo has been shown to have antioxidant and vascular effects. Ginkgo has been shown in some studies to slow visual field progression in normal tension glaucoma patients.27, 28 However, follow-up studies with the same design failed to replicate the findings. More studies are needed to determine whether ginkgo is an effective adjuvant treatment in POAG.

Saffron Extract:

Increasing evidence from both experimental models and clinical studies in patients supports the neuroprotective effect of saffron components in neurodegenerative conditions due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and antioxidant properties. It has been shown to reduce microglial activation, regulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, and prevent ganglion cell death.29 While more evidence is needed, this is on the horizon for future adjuvant treatments for POAG.

Mitigating the effects of oxidative stress and inflammation in glaucoma through diet and lifestyle factors represents exciting new avenues for research and clinical practice. As the AREDs trials showed us that nutrients can mitigate the course of age-related macular degeneration, specific nutrient protocols for glaucoma therapy may be next on the horizon. In the meantime, patients can be encouraged to increase vegetable and fruit intake, fatty fish and omega 3s, nuts, seeds, berries, polyphenols, antioxidants, and micronutrients.

References

1 The U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators. The State of U.S. Health, 1990-2016. Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Among US States. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444-1472.

2 Almasieh M, Wilson AM, Morquetts B, et al. The molecular basis of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012; 31:152-181.

3 McMonnies C. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, glaucoma, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Optom 2018; 11:3-9.

4 Veach J. Functional dichotomy: glutathione and vitamin E in homeostasis relevant to primary open-angle glaucoma. Br J Nutr 2004; 91:809-829.

5 West AL, Oren GA, Moroi SE. Evidence for the use of nutritional supplements and herbal medicines in common eye diseases. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 141:157-166.

6 Lucius R, Sievers J. Postnatal retinal ganglion cells in vitro: protection against reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced axonal degeneration by cocultured astrocytes. Brain Res 1996; 743:56-62.

7 Mazaffarieh M, Grieshaber MC, Orgul S et al. The potential value of natural antioxidant treatment in glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 2008; 53:479-505.

8 Liu Q, Ju WK, Crowston JG et al. Oxidative stress is an early event in hydrostatic pressure induced retinal ganglion cell damage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48:4580-4589.

9 Wax MB, Tezel G. Immunoregulation of retinal ganglion cell fate in glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 2009; 88: 825-830.

10 Tezel G, Wax MB. The immune system and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004; 15: 80-84.

11 Nucci C, Russo R, Martucci A et al. New strategies for neuroprotection in glaucoma, a disease that affects the central nervous system. Eur J Pharmacol 2016; 787: 119-126.

12 Tanito M, Kaidzu S, Takai Y et al. Association between systemic oxidative stress and visual field damage in open-angle glaucoma. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 25792.

13 Abu-Amero KK, Kondkar AA, Mousa A et al. Decreased total antioxidants in patients with primary open angle glaucoma. Curr Eye Res 2013; 38: 959-964.

14 Yoo TK, Oh E, Hong S. Is vitamin D status associated with open-angle glaucoma? A cross-sectional study from South Korea. Public Health Nutr 2014; 17: 833-843.

15 Yuki K, Murat D, Kimura I et al. Reduced serum vitamin C and increased uric acid levels in normal-tension glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010; 248: 243-248.

16 Jabbehdari S, Chen JL, Vajaranant TS. Effect of dietary modification and antioxidant supplementation on intraocular pressure and open-angle glaucoma. European Journal of Opthalmology 2021; Vol. 31(4) 1588-1605.

17 Schnebelen C, Pasquis B, Salinas-Navarro M et al. A dietary combination of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids is more efficient than single supplementations in the prevention of retinal damage induced by elevation of intraocular pressure in rats. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009; 247: 1191-1203.

18 Schnebelen C, Fourgeux C, Pasquis B et al. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce retinal stress induced by an elevation of intraocular pressure in rats. Nutr Res 2011; 31: 286-295.

19 Nguyen CT, Bui BV, Sinclair AJ et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids decrease intraocular pressure with age by increasing outflow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 756-762.

20 Nguyen CT, Vingrys AJ, and Bui BV. Dietary omega-3 deficiency and IOP insult are additive risk factors for ganglion cell dysfunction. J Glaucoma 2013; 22: 269-277.

21 Downie LE, Vingrys AJ. Oral omega-3 supplementation lowers intraocular pressure in normotensive adults. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2018 May 1;7(3):1.

22 Kang JH, Willett WC, Rosner BA et al. Association of dietary nitrate intake with primary open-angle glaucoma: a prospective analysis from the nurses’ health study and health professionals follow-up study. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134: 294-303.

23 Vergroesen JE, de Crom TOE, van Duijin CM et al. MIND diet lowers risk of open-angle glaucoma: the Rotterdam study. Eur J Nutr. 2023 Feb;62(1):477-487.

24 Martucci A, Mancino R, Cesareo M et al. Combined use of coenzyme Q10 and citicoline: A new possibility for patients with glaucoma. Front Med 15 December 2022. Sec Ophthalmology Volume 9.

25 Martucci A. Evidence on neuroprotective properties of coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of glaucoma. Neural Regeneration Research February 2019. 14(2):197.

26 Deichmann R, Lavie C, Andrews S. Coenzyme Q10 and statin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Ochsner J. 2010 Spring; 10(1): 16-21.

27 Lee J, Sohn SW, Kee C. Effect of ginkgo biloba extract on visual field progression in normal tension glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2013; 22: 780-784.

28 Quaranta L, Bettelli S, Uva MG et al. Effect of ginkgo biloba extract on preexisting visual field damage in normal tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2003; 110:359-362.

29 Fernandez-Albarral J. Saffron benefits for eye diseases. Acta Ophthalmologica 20 December 2022. Volume 10, issue S275.