March 4, 2024

How do you handle the patient who comes in with intractable floaters? These are people who complain of difficulties doing simple daily activities such as driving, reading, or working on a computer. They can be so debilitating they can affect a person’s ability to do their job. These are often myopic patients who inherently have more floaters and/or our presbyopic patients following a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD).

For many years, we trivialized the effect the floaters had on the quality of life of our patients. Probably because we really didn’t have any accessible treatments. Note the use of the word “accessible,” because we did have a treatment – vitrectomy. The problem is you couldn’t really find a retinal specialist willing to do a vitrectomy on a patient with intractable floaters. Probably for good reason. Prior to advances in microsurgical tools and techniques, vitrectomy was a pretty invasive procedure.

Pars Plana Vitrectomy – the Essentials

The traditional 20-gauge vitrectomy consists of making three ports in which small sclerotomies are made 3-4 mm behind the limbus on the nasal and temporal side of the globe. In one port a vitreous cutter is inserted into the vitreous cavity to remove the vitreous. Another port is used to infuse fluid to maintain IOP, and the third port is used to insert a light source to illuminate the posterior segment. For close to 30 years, 20-guage vitrectomy was the standard, with the gauge referring to the size of the instruments that are inserted into the sclerotomies. Sclerotomies created for 20-gauge instruments need to be sutured at the end of the procedure.

Postoperatively, these patients were uncomfortable, often being able to feel the sutures, and the eyes were quite red. It’s very evident when looking at a patient after a vitrectomy that they had a pretty significant eye procedure. As with any incisional surgery, there is an inherent risk for endophthalmitis, retinal tears and detachment, and hypotony, among others. Vitrectomy can also accelerate the development of cataract formation.

Given the invasive nature of a vitrectomy and the inherent risks, a retinal specialist wouldn’t even consider the idea of doing a vitrectomy for floaters. Moreover, once patients understood what the procedure involved and the risks, they would choose to live with the symptoms. However, as technology advanced, the instrumentation and techniques used in vitrectomy evolved. Vitrectomy instruments have become much smaller, with 25-gauge and 27-gauge becoming the standard. Instead of 0.9 mm sclerotomies for 20-gauge vitrectomy, the incisions are now much smaller, 0.4 to 0.5 mm in diameter. There are no incisions in the conjunctiva and no cuts into the sclera so sutures are not needed. Trocar cannula systems, which consist of a hollow cannula inserted into the sclerotomies, are now used as a means of inserting the instruments. Once the trocars are removed at the completion of the procedure; the wounds are self-sealing without sutures. This has resulted in patients having an overall improved experience with less inflammation, discomfort, and redness. This has opened the door for other “less important” opportunities for vitrectomy, such as a “floaterectomy.” Has it become a reasonable option or are the risks of vitrectomy still too high?

How Common Are Floaters?

The fact is floaters are very common. In an international study that evaluated the prevalence of floaters in a community sample of smartphone users in the U.S., Australia, Israel, and the U.K., of a total of 603 people who completed an electronic survey, 76% reported floaters and 33% found them to be causing visual impairment.1

Given the high number of patients presenting with symptoms of floaters, and with advances in vitrectomy, more and more retinal specialists are doing vitrectomy for floaters, and the outcomes are quite good. However, as more and more procedures are being performed, we are learning more about the different nuances that may be unique to patients who are undergoing vitrectomy specifically for floaters.

What is a Floaterectomy?

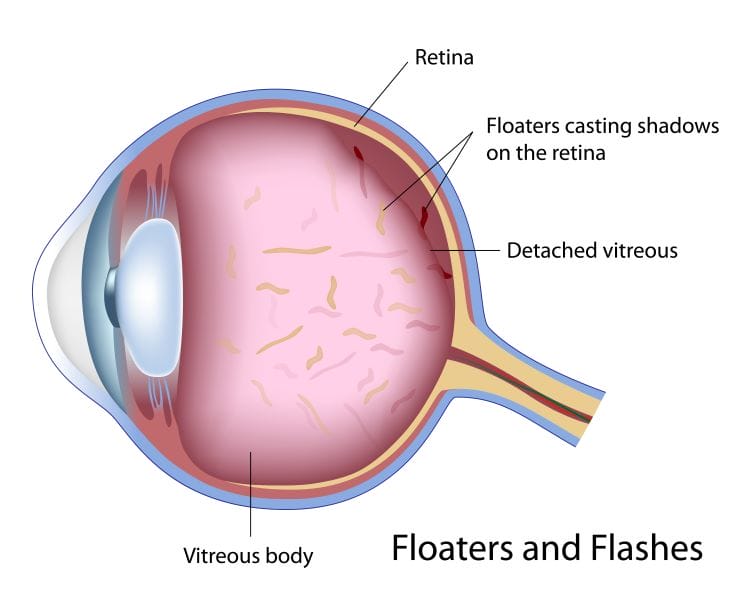

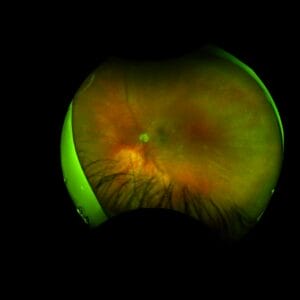

The basic concept around vitrectomy for floaters is very simple. By removing the posterior vitreous, the floaters that are responsible for the symptoms are contained within the central vitreous, get removed with the vitrectomy. In a patient with a PVD, this can be straightforward as there is minimal traction on the retina. What about in patients who have symptomatic floaters but do not have a PVD? Does the surgeon induce a PVD at the time of the vitrectomy to minimize any traction on the retina that could ultimately induce a retinal tear or detachment? Some retinal specialists will try to induce a PVD while others think this can actually increase the risk of a complication.

There is also a question of removing the anterior vitreous as a means of limiting traction on the peripheral retina. Though anterior vitrectomy may reduce the traction on the peripheral retina, it may accelerate the development of a cataract. As a result, some retinal surgeons will leave 3-4 mm of the vitreous gel behind the lens as a means of reducing this risk.

So how successful is vitrectomy as a treatment for floaters? In one retrospective study of 66 eyes, the floaters resolved in 65 of the 66 eyes (98.5%) that had vitrectomy. In this study the average duration of coping with floaters was 30 months. A PVD was responsible in 67% of eyes, and myopia-induced floaters were responsible in 28%. No patients (0/66; 0%) developed retinal breaks, hemorrhage, infection, or glaucoma (three month – three years). In eyes that did not have a PVD at the time of surgery (22 eyes), there were no retinal breaks or detachments. Only 7/36 (19%) phakic eyes developed cataracts requiring surgery, an average of 16.5 months post-vitrectomy (7/36 [19%] vs. 18/36 [50%]).2

In another study looking at the long-term safety and efficacy of limited vitrectomy for floaters in 195 eyes that underwent 25-gauge vitrectomy without inducing a PVD and preserving 3-4 mm of the retrolental vitreous in phakic eyes, the authors found a reduced ecodensity of the floaters by 94%, and the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ) improved by over 19%. Unfortunately, in this study there were three retinal tears (1.5%) and three retinal detachments (1.5%) that underwent successful repair. Clinically significant vitreous hemorrhage developed in two patients (1%), clearing spontaneously. Cataract surgery occurred in 21 of 124 patients (16.9%) and none in patients younger than 53. The authors concluded that limited vitrectomy for “vision degrading vitreopathy” decreases vitreous echodensity, improves patient well-being, and improves visual acuity.3 The long-term safety and efficacy profiles suggest this may be a safe and effective treatment for clinically significant vitreous floaters.

Serious Retinal Complications a Risk

Perhaps the best analysis regarding safety comes from the IRIS registry in which 17,615 eyes were evaluated for a vitrectomy specifically for symptoms of vitreous opacities. The authors looked at ICD9 and ICD10 claims for patients who returned to the operating room within one year after having a vitrectomy for floaters. Of the 17,615 eyes that had vitrectomy, 2,187 (12.4%) returned to the operating room for cataract surgery within one year. Most concerning, however, were 643 eyes (3.7%) that returned for a non-cataract procedure of which 457 eyes (2.6%) required repair of retinal detachment. So, when considering vitrectomy for intractable floaters, patients need to know the real-world risks for needing cataract surgery following vitrectomy as well as the risk for a serous retinal complication such as a retinal detachment, which is around 2.5%.4 Most retinal specialists would consider that risk too high.

The Ideal Patient and Not So Ideal Patient

Which patients should be considered for vitrectomy for floaters? Most surgeons want to ensure patients are truly impacted and that the symptoms are not transient. It is also important that patients understand the risks including the potential of developing a cataract or a more serious retinal complication. So, duration of symptoms is important with many surgeons waiting until patients have been symptomatic for at least four to six months. The ideal patient would be pseudophakic and already having developed a PVD. Less ideal patients are younger, phakic, and have an intact vitreous. Certainly, any patients with peripheral retinal pathology are at an increased risk for retinal complications and though not a contraindication, are often treated prior to undergoing vitrectomy.

The era of modern medicine has led to numerous breakthroughs including microsurgical vitreous techniques. This has led to better visual and anatomic outcomes in patients who undergo vitrectomy for numerous sight-threatening conditions. Floaterectomy, a procedure that was once considered taboo, is now more commonly done with excellent outcomes. It offers our patients a reasonable treatment option with a speedy recovery. However, retinal specialists still need to be selective in who they perform this procedure on as the risks for a serious retinal complication are not insignificant.

Once again it puts optometry in the driver’s seat in identifying these patients and making sure they understand the treatment options for dealing with floaters, as well as the potential risks. However, not every retinal surgeon is on board with floaterectomy, so it is the primary eye care provider’s responsibility to know who in the community is doing this procedure and to make sure patients are directed to the right surgeon at the right time.

References

1 Webb BF, Webb JR, Schroeder MC, North CS. Prevalence of vitreous floaters in a community sample of smartphone users. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(3):402-405.

2 Wa C, Yee, K, Huang L, et al. Long-term safety of vitrectomy for patients with floaters. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science June 2013, Vol.54, 2142.

3 Sebag J, Yee KMP, Nguyen JH, et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Limited Vitrectomy for Vision Degrading Vitreopathy Resulting from Vitreous Floaters. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018 Sep;2(9):881-887. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2018.03.011. Epub 2018 May 11.

4 Rubino, SM, Parke DW, Lum F. Return to the Operating Room after vitrectomy for vitreous opacities: Intelligent Research in Sight Registry Analysis. Othalmol Retina. 2021 Jan;5(1):4-8.doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.07.015.