July 26, 2023

The evolution of optometry into medical eye care began to take off in the early 1970s when Rhode Island became the first state to be granted diagnostic privileges, followed a few years later by West Virginia and North Carolina. More states slowly followed with Maryland being the last state to be granted the right to use topical diagnostic drops in 1989. The use of therapeutics also helped establish optometry as a medical profession when in 1976, West Virginia became the first state that optometrists could prescribe prescription eye drops to treat eye disease1.

Certainly, this evolution didn’t happen by accident. There are numerous stories of ODs who worked in the armed forces, VA hospitals and the like, who began using diagnostic and therapeutic medications much earlier, and this likely laid the groundwork for organized optometry to move forward legislatively.

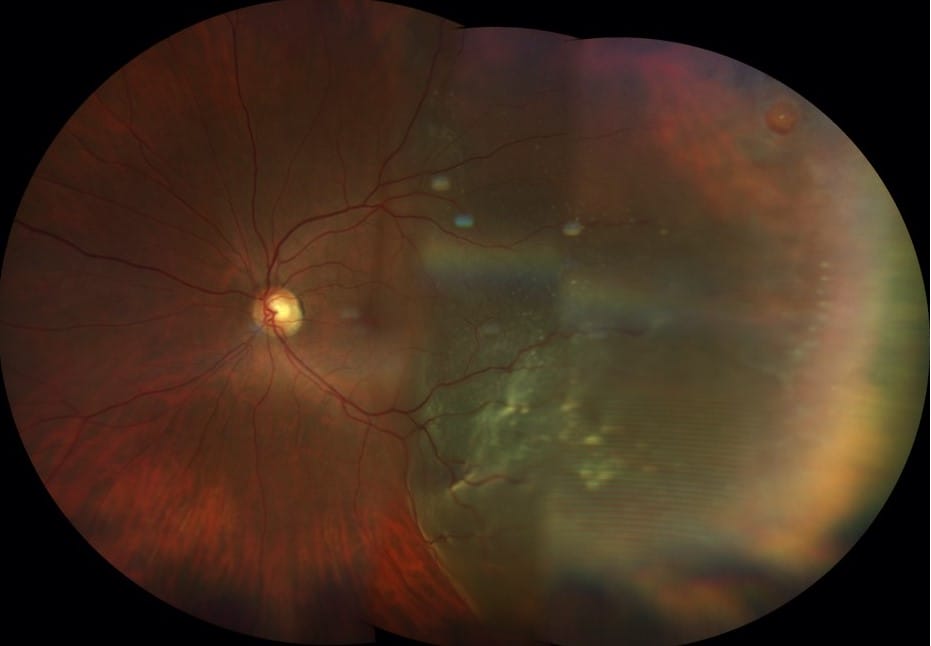

The increased scope of expansion also resulted in a greater responsibility for optometrists to not just detect, ascertain, or recognize abnormalities, as was often written in state laws, but to in fact diagnose conditions of the eye and visual system. Indeed, the use of diagnostic agents and the need to diagnose carried with it potential medical and legal implications. The failure to diagnose a retinal detachment or malignant melanoma because a patient wasn’t dilated could result not only in significant visual morbidity but the potential loss of life if the uveal melanoma wasn’t recognized.

As a result, the dilated eye exam became an essential part of a comprehensive eye exam, even specifically being called out in many state laws. Despite this, there continues to be a strong aversion to routine dilation, mostly by the patients but by the providers, too. The patients complain of extreme photosensitivity and blurred vision, often resulting in the inability to perform routine tasks for several hours, such as driving and reading.

For the provider, it also becomes a time element as patients have to wait longer for the dilating drops to work, which can result in patients complaining about having to wait, and then hearing the direct feedback from the patient about how uncomfortable they are with the dilation. It can be hard to justify to healthy patients who may come in with the expectation of a quick exam, who need to get back to work, pick up their children, or do whatever critical task that’s been planned. And now it can’t be done or becomes very uncomfortable for them to do.

The Emergence of Widefield and Ultra-Widefield Imaging

The evolution of widefield imaging and ultra-widefield imaging has been an important advancement in allowing providers the ability to see far out into the peripheral retina without needing to dilate. Because the quality is so good, it has blurred the lines between needing to dilate or not dilating and just using widefield imaging or ultra-widefield imaging, especially in asymptomatic, healthy patients without risk factors.

There is no consensus on how often patients under a certain age should be dilated. Moreover, the incidence of meaningful fundus lesions in asymptomatic patients is extremely low. In one study of more than 3,800 asymptomatic patients, only 30 (2.73%) had clinically significant fundus lesions, and only three were outside the view of a direct ophthalmoscope. Widefield imaging was not used in this study but would have likely detected these lesions based on their location. Not surprisingly, the incidence of clinically significant retinal pathology increased with age from 0.8% in patients younger than age 20 to 8.9% for those older than age 60.2

To Dilate or Not Dilate

The argument for dilating is mostly based on the medical legal ramifications of not dilating; the potential of missing retinal pathology and how you would justify the reason for not dilating in front of a judge. The fact remains, a dilated eye exam is still considered to be the standard of care. Moreover, the definition of an eye exam, in any instance, does not include fundus photography. 3 No doubt, the presence of retinal pathology or risk factors necessitates the need for a dilated fundus exam regardless of how good ultra-widefield imaging is.

There seems to be a direct relationship between the type of practice setting and how often or when patients get dilated. In an ophthalmology practice or hospital setting, it seems virtually everybody receives a dilated eye exam, with little exception, and patients expect this. Certainly, any new patient or those coming in for an annual follow-up will get dilated, as well as those with chronic eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy. It’s likely not the same in a typical primary eye care or retail/commercial setting. Surely the new patient will get dilated and certainly those with chronic conditions, but does a healthy, young patient under a certain age need to be dilated, or dilated every year? What’s more, in these settings, patients aren’t expecting to be dilated. Even the new patient might refuse, which puts the provider in a difficult situation. Will ultra-widefield imaging suffice?

I think this speaks to the culture of a practice. The culture in an ophthalmology or hospital setting sets the expectation of a more medical eye exam that includes a routine dilated exam. For some patients, that’s why they may choose to be seen in those settings, even healthy patients. Others may choose a more retail setting because the culture of those practices are perceived to be less medical, and for someone who feels they only need glasses or contact lenses, that’s sufficient for their needs. Many private practices have managed to blend both worlds; having developed a culture of being a medical practice while also making sure the optical needs of the patient are met.

A New Era for Health Care

We are witnessing a paradigm shift in the current era of health care. Health care and eye care in particular, have evolved to become more of a volume business. As reimbursements have gone down, there is a need to see more patients. Coupled with an aging population, and an insufficient supply of physicians to keep up with the demand, health care providers are seeing more and more patients on their schedules. It’s not uncommon for a subspeciality ophthalmologist to see 70, 80, or even more patients in a day. You can’t help but ask how is that even possible? Fortunately, advances in imaging technology, such as OCT and ultra- widefield imaging have helped without any significant compromise on quality. In these settings, many patients aren’t being dilated, unless there is an indication. Even in the setting of macular disease, the ability of an OCT to provide a high-quality scan in the absence of a dilated pupil is remarkable.

Optometry’s volumes are not nearly as high, but in some practice settings the volumes can be quite significant, making it challenging for a comprehensive provider to manage all aspects of eye care, not just the glaucoma, or the dry eye, or the cataract, but everything, including ensuring their optical needs are met.

The reality is the dilated eye exam has become a symbol for a good comprehensive eye exam, regardless if a dilated pupil actually adds to the quality of the eye exam. For instance, many protocols for managing diabetic retinopathy call specifically for a dilated eye exam even though being able to accurately detect and categorize the level of diabetic retinopathy is better with widefield imaging or ultra-widefield imaging, regardless if the pupil is dilated or not. No doubt many of these protocols were written in an era when widefield imaging didn’t exist, but now given the high quality of imaging, how important is it really, especially given the epidemic proportion of DR around the world.

Binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy through a dilated pupil remains the gold standard for a comprehensive eye exam, and widefield imaging/ultra-widefield imaging has emerged, not just as an important complement to a dilated fundus exam, but in some instances can be a substitute. As of now, it’s still up to the provider to decide on a case-by-case basis if the patient actually needs to be dilated and what value that provides beyond just the medical and legal ramifications.

References

1 Optometry’s Essential and Expanding Role in Health Care: Assured Quality and Greater Access for Healthier Communities. White Paper June 12, 2019. Accessed July 15, 2023.

2 Pollack AL, Brodi SE. Diagnostic yield of the routine dilated fundus examination. Ophthalmology 1998 Feb;105(2):382-6.

3 Corcoran SL. CODING Q&A: The Decision to Dilate, “Not mandatory” does not mean unnecessary or not recommended. Retinal Physician. September 2022.