August 1, 2023

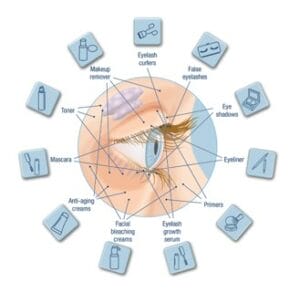

Cosmetics play an essential role in enhancing our patient’s appearance, increasing self-confidence, and in some cultures, boosting status. From mascara, eyeliner, and shadows to beauty habits such as lash extensions and serums, and finally lotions and potions for skin, there is a great need for education for us and our patients. We have the gift of utilizing a microscope to truly see the consequences of what our patients unknowingly may be doing to sabotage their own eye health. Let’s begin by filling in some gaps.

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) was written in 1938 with the intent of protecting the public and to oversee as well as regulate the production, sale, and distribution of food, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics. There has been no update for cosmetics since then, yet the cosmetic industry has greatly changed and expanded. How do we begin to navigate a multibillion-dollar cosmetic industry that spends billions marketing to our patients? We have to be an advocate for our patients, arm them with better data, and offer transparency where we can. One fact that I find astounding is that the FDCA only bans 11 ingredients in the United States, while the European Union (EU) bans more than 1,600 ingredients. The U.S. bans the following 11 ingredients:

- bithionol

- chlorofluorocarbon propellants

- chloroform

- halogenated salicylanilides (di-, tri-, metabromsalan and tetrachlorosalicylanilide)

- hexachlorophene

- mercury compounds

- methylene chloride

- prohibited cattle materials

- sunscreens in cosmetics (subject to product’s labeling)

- vinyl chloride

- zirconium-containing complexes

Here’s a list of ingredients banned in the EU but still allowed in U.S. products. Many on this list can be harmful to the ocular surface:

- formaldehyde

- hydroquinone

- triclosan

- lead

- parabens

- petroleum distillates

- phthalates

- selenium sulfide

- quaternium-15

When looking at the research available today, these ingredients also have been found to be harmful to the ocular surface:

- benzalkonium chloride BAK

- butylene glycol at high concentrations

- ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)

- formaldehyde-donating preservatives, even at low concentrations

- isopropyl cloprostenate, PGAs. Unknown concentration in over-the-counter eye lash growth serums

- parabens (methyl-, isobutyl-, propyl- and others) at certain concentrations

- phenoxyethanol: at certain concentrations

- cis-retinoic acid: impairs survival and differentiation of HMGEC in cell culture but not HCEC

I like to list these eight ingredients on a handout for my patients. I would encourage you to do the same. This way you aren’t relying on specific brands but giving patients information they can use across all beauty products.

Understand the Product Labels

It’s not only the ingredients that can be a problem. The label and terminology can also be a problem. There are lots of marketing terms that have no definition including: clean, natural, hypoallergenic, ophthalmology tested, among others. One study that looked specifically at hypoallergenic products evaluated 187 products labeled as “hypoallergenic,” “dermatologist recommended/tested,” “fragrance free,” or “paraben free,” 167 (89%) products contained at least one contact allergen, and 117 products (63%) contained two or more contact allergens present in the North American Contact Dermatitis standard screening series.1,2 Knowing what we are looking at, asking great questions, and developing strategies will help us with our foundational knowledge so that we can expand. Begin by identifying threats. For example, mascara can be problematic if it contains ingredients that are harmful, if it’s waterproof, or if it contains nylon to lengthen lashes. Eyeliner placement can damage meibomian glands by putting it directly on the orifice.

Figure 1A shows correct placement of eyeliner on the lower lid. Figure 1B depicts tightlining, a habit that can be harmful to delicate meibomian glands.

Figure 1A shows correct placement of eyeliner on the lower lid. Figure 1B depicts tightlining, a habit that can be harmful to delicate meibomian glands.

So, what should we be asking our patients about their cosmetic use? Here are some great questions that aren’t intimidating or off-putting:

- Wow! Your lashes are really long, are they natural? (Lucky them☺) or are you using a serum to make them look that way?

- How do you clean your lash extensions?

- Do you wear eye makeup?

- How do you remove your makeup?

- Do you ever sleep in your eye makeup?

- Did you know many of the products we use around our eyes could cause eye health issues today or in the future?

- Are your lashes thinner, shorter, more brittle than you would like them to be?

- Do your eyelids bother you?

- Did you know the delicate eye area is the most common place for skin cancer? Are you wearing protective sun ophthalmic lenses?

While our patients will often make choices that enhance their appearance, they often have no idea of the long-term effects of said choices. It’s essential as eye care providers for us to understand the potential risks posed to ocular surface health. By being aware of the risk factors we can communicate that to our patients.

Easy Beauty Habits that We Can Share with Our Patients:

- Throw makeup away in a timely manner, three months and certainly if it’s expired. For mascara, I look for smaller tubes that can be thrown away monthly.

- Don’t share makeup (especially good to have this conversation with the tweens/teens).

- Wash makeup brushes weekly.

- Don’t tightline.

- Remove eye makeup EVERY night.

- Choose eye makeup remover that is water based not oil based.

- Don’t utilize waterproof mascara because of the ingredients and because it’s difficult to remove

Figure 2 TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of cosmetics on the ocular surface.

Figure 2 TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of cosmetics on the ocular surface.

Great resources:

Sullivan et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37061220/

The EWG site: https://www.ewg.org

The Cosmetic Ingredient Review: https://www.cir-safety.org

References

1 Hamann CR, Bernard S, Hamann D, Hansen R, Thyssen JP. Is there a risk using hypoallergenic cosmetic pediatric products in the United States? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:1070–1.

2 Rubin CB, Brod B. Natural Does Not Mean Safe—The Dirt on Clean Beauty Products. JAMA Dermatol.2019;155(12):1344–1345. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2724