peer reviewed

January 4, 2024

Geographic Atrophy (GA) has recently taken center stage in eye care due to two recent FDA approvals for its treatment. Although the excitement around treatment options is new, the actual disease and its burden are not and have been often overlooked in the past. It is estimated that GA affects in the vicinity of one million Americans.1,2 However this number is likely lower than the real prevalence because of historical under-reporting due to lack of definitive treatment.

The other misconception about GA other than its lack of pervasiveness, is that it is slow moving and doesn’t ultimately affect function in many people. To the contrary, research tells us that 67% of people with bilateral GA will lose their ability to drive in just over a year and a half, and 40% will lose two lines acuity in an average of just under two and a half years.3 Besides just the visual burdens that GA can cause, it can definitely weigh on a person’s mental well-being. We know that it can have a severely negative impact on quality of life, especially in people with central vision loss.4

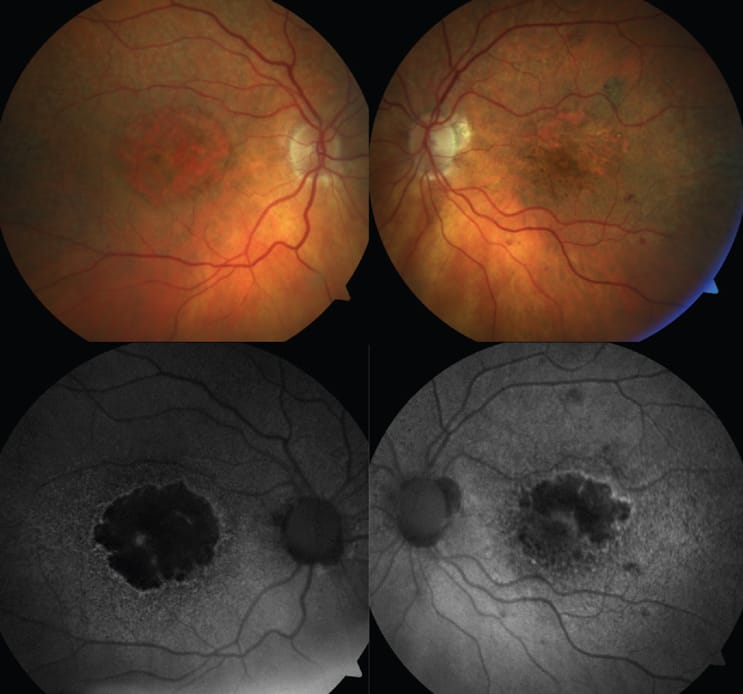

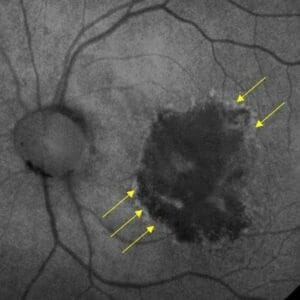

So, how do we identify GA? Oftentimes it is seen upon clinical exam but can be more clearly defined and monitored by using optical coherence tomography (OCT) and/or fundus autofluorescence (FAF). These are the modalities most often used in clinical trials for identifying presence and progression of GA lesions either in the macula or outside. Imaging is so important, as best corrected visual acuity is poorly correlated with lesion size, even as lesions grow and functional vision may decline.5 Patients may have extensive GA and still be seeing 20/20 on a Snellen chart, although their true functional vision will not be doing well. Another measure of disease extent could be area of scotoma. Interestingly, up to 40% of people with definite deficits in their central field will not detect them using an Amsler grid. 6 Something as simple as a “face field” could help to identify extent of scotoma. 7

Identifying GA as early as possible is important to allow for appropriate follow-up and potential referral for treatment.8 There are different factors regarding GA such as lesion size, location, whether it is multifocal, and imaging appearances that can help “predict” progression/outcome.9 Many of us are not as comfortable with diagnosing GA as we are with other conditions due to infrequency of seeing it in our offices or previous complacency due to lack of call-to-action of treatments. On OCT, important signs may include hypertransmission defects or retinal pigment epithelial disruptions. On FAF, we need to be looking for areas of hypo-autofluorescence as well as areas of hyper-autofluorescence, which may indicate activity.

The causes of GA are different from that of wet AMD and as such are ultimately treated differently. One of the main pathways indicated in GA is the complement pathway.10 An entire article could be dedicated to this, but for the purpose of this article, I will just point out the potential importance of C3 and C5 in the ultimate formation of inflammation and cell lysis in GA. Accordingly, this is where the approved treatments target to stop the cascade, delay, or slow lesion growth. Studies show that the approved treatments can slow growth from between 17% and 35% over a two-year period through intravitreal injections every one to two months.

With treatment options come new responsibilities for ODs. Now the act of identification of GA is not enough. We need to educate our patients and give them the opportunity to see a retina specialist to potentially treat their GA. Of note is that not all patients may be ideal candidates for treatment or even want treatment as it is chronic and sometimes not perceived as needed. If somebody is 20/20 in both eyes, then the idea of treatment may be daunting, and our education is even more important. As such, not all patients referred to a retina specialist will ultimately be treated, but every patient will need continued comanagement with you, their primary eye care provider. Partnering with a retina specialist and knowing their treatment preferences/patterns can help to make even more appropriate referrals. This can be accomplished through email, phone, or in person to better understand their practice and so the retina specialist can understand your desired level of involvement in care. Having this understanding will help you feel confident and empowered in how you help the patient along their journey. We all need to realize the burden on us to appropriately educate in order to prepare patients for their journey ahead, whether or not it includes immediate treatment.

As we are more comfortable with what to expect from the retina specialist, this allows better education of our patients and for us to better prepare them for their visits to the retina specialist. It is important to help with expectations, especially that treatment of GA doesn’t improve vision and will not completely halt its progression. The goal is to slow progression to preserve vision and functionality as long as possible. By sharing this with your patient, it will ultimately lead to a more satisfactory outcome for everybody involved.

With the shift to an era of GA treatment comes an exciting time. Opportunities to help along the way are vast and only shine a light on the importance of integrated care between primary eye care and specialty care.

This content is independent editorial sponsored by Astellas. Astellas had no input in the development of this content.

References

1 Friedman et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):564-572.

2 IQVIA Medical Claims (Dx) Data Jan’20 –Dec’21: 24 Months: Iveric Bio; 2022.

3 Chakravarthy et al. Characterizing Disease Burden and Progression of Geographic Atrophy Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(6):842-849.

4 Madheswaran G, et al. Impact of living with a bilateral central vision loss due to geographic atrophy—qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e047861. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047861

5 Sunness et al. The long-term natural history of geographic atrophy from age-related macular degeneration: enlargement of atrophy and implications for interventional clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):271-277.

6 Fine EM, Rubin GS. Reading with simulated scotomas: Attending to the right is better than attending to the left. Vision Research. 1999;39:1039–1048.

7 Sunness, J. Face Fields and Microperimetry for Estimating the Location of Fixation in Eyes with Macular Disease. J Vis Impair Blind. 2008 Nov; 102(11): 679–689.

8 Armento A, Ueffing M, Clark SJ. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(10):4487-4505.

9 Flaxel CJ, Adelman RA, Bailey ST, et al. Age-related macular degeneration preferred practice pattern(R). Ophthalmology. 2020;127(1):P1-P65.

10 Xie CB, Jane-Wit D, Pober JS. Complement membrane attack complex: new roles, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic targets. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(6):1138-1150.

Photo courtesy of Anna Bedwell, OD