peer reviewed

November 29, 2023

The late Sidney Poitier poignantly noted that, “Hope is the eternal tool in the survival kit of mankind.” I couldn’t agree more. Progressive and blinding diseases are not new. However, within my decade of clinical practice, I’ve watched the interventional tool bag blossom into a large and expansive toolbox filled with an arsenal of tangible therapeutic options that can be utilized in the management of diseases whose physical and psychological burden often left patients feeling helpless and hopeless.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of blindness among elderly individuals in the developed world and currently impacts approximately 20 million American lives.1 The pathogenesis of AMD is impacted by myriad factors that include genetics, aging, oxidative stress, and inflammation. The presence of geographic atrophy (GA) defines the stage of non-exudative AMD and, until this year, there was no treatment for this functionally aggressive disease.

Although GA contributes to the $2.9 billion annual economic burden from vision loss, its impact reaches far beyond the visual system. Patients with severe vision loss not only suffer from higher rates of clinical depression and anxiety than their sighted peers, but they also sadly experience a significant increase in all-cause mortality.2-3

Doctors of optometry play a critical role in the identification and referral of GA patients who may benefit from new treatments. Dispelling myths, understanding distinct biomarkers and having a plan for these patients is critical to appropriately caring for this vulnerable patient population.

What Do We Think? (The Myths)

Non-exudative AMD is commonly thought to progress in a “slow and steady” fashion. However data from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) reflects a relatively “fast and furious” timeline for GA changes, with 2.5 years as the median time from initial diagnosis to foveal involvement.4

Another myth regarding GA is that visual acuity is the best indicator of disease progression. As an OD who lives in the glaucoma space, I am acutely aware that this notion is simply untrue. Functional vision, such as the ability to safely drive a car or comfortably read a tablet, can be significantly impacted in patients with para-foveal scotomas and diminished contrast sensitivity.

Although certain blinding diseases such as GA have a greater prevalence in particular patient populations, it is important to thoroughly evaluate all patients with atypical retinal findings. Failure to do so may result in a missed GA diagnosis and prevent patient access to therapeutics that may preserve vision and maintain quality of life.

What Do We See? (The Biomarkers)

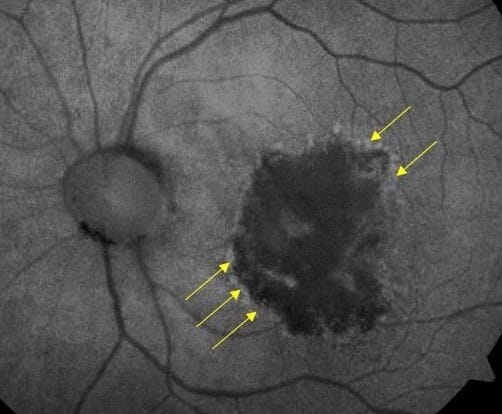

GA traditionally forms as irregular, parafoveal patches that are observable on fundoscopy and easily captured on color fundus photos (CFP) (Figure 1). Lesion area, number of lesions, shape, location, and direction of growth in relation to the fovea all have predictive power in the rate of disease progression.

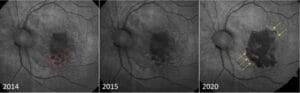

Since AMD impacts lipofuscin, fundus autofluorescence (FAF) is an ideal imaging modality for GA. The atrophic lesions appear dark, or hypofluorescent, when captured on FAF (Figure 2). These areas may expand and coalesce over time, gradually encroaching and eventually involving the fovea. When evaluating FAF, it’s important to note the presence of hyperfluorescence at lesion edges, as these are associated with faster disease progression.5

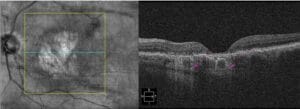

SD-OCT is a complementary imaging modality that can easily capture the unique choroidal hyper-transmission defects (hyperTD) present in GA (Figure 3). This biomarker resembles vertical beams of light because the OCT signal penetrates past the disrupted, defective RPE and into the choroid. Additionally, some platforms have the capability to measure lesion size and calculate enlargement rates over time.

Near-infrared imaging (NIR) captures the outer retina and can be valuable in documenting the loss of photoreceptors. NIR is particularly useful in capturing the presence of reticular pseudodrusen (RPD). These subretinal drusenoid deposits, commonly found in the superior macula, can be difficult to image with other platforms and represent an increased risk of AMD progression.6

Two terms that are used in the classification of GA are incomplete retinal pigment epithelium and outer retinal atrophy (iRORA) and complete retinal pigment epithelium and outer retinal atrophy (cRORA). These describe the extent of atrophy, with the conversion of the former to the latter representing the rate of change.

No Longer Stay, Pray, and Wait

While first-in-class therapeutics for the treatment of GA moved through the clinical pipeline, I heard GA management described as, “stay (with the OD), pray, and wait.” Despite the significant amount of vision loss that GA patients experienced, the only tangible actions that we could take were active referrals to low vision resources and holding space with a kind and empathetic ear.

The fundamental tenet of that paradigm changed this year with the FDA approval of pegcetacoplan (Syfovre, Apellis Pharmaceuticals) and avacincaptad pegol (Izervay, Astellas Pharma) for the treatment of GA. Pegcetacoplan and avacincaptad pegol, both administered by intravitreal injection, target the complement cascade at C3 and C5, respectively. These medications do not completely halt the progression of GA, but they have been shown to statistically slow the progression of lesion expansion.

The goal of current GA therapies is EARLY intervention. This will only occur with early detection and active referrals to retinal surgeons from the optometric community. Collaborative and informed care will prevent lesions from damaging the fovea, thus mitigating the devastating vision loss experienced by previous generations of GA patients.

What Do We Do? (Clinical Plan)

Create a plan to screen new and existing non-exudative AMD patients for GA. Utilize your imaging modalities, appropriately code and actively diagnose. Have open and honest discussions of the risks and benefits of these new interventions. Give the patient the opportunity to accept your referral to retina specialists for maximized care.

As primary eye care providers, optometrists are uniquely poised to not only diagnose, but more importantly, counsel and actively refer this growing population of patients. Staying abreast of the developments within the landscape of macular degeneration is critical to ensuring we are providing the highest quality of care within our communities.

We have always had the power to provide thoughtful and compassionate care. We have the power to provide accurate diagnosis and timely referrals. Now, above all else, we have the power to offer GA patients hope.

This content is independent editorial sponsored by Astellas. Astellas had no input in the development of this content.

References

1 Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202–1208.

2 Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang P, et al. The Economic Burden of Vision Loss and Blindness in the United States. Ophthalmology. Apr 2022;129(4):369-378.

3 Ehrlich JR, Ramke J, Macleod D, Burn H, Lee CN, Zhang JH, Waldock W, Swenor BK, Gordon I, Congdon N, Burton M, Evans JR. Association between vision impairment and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021 Apr;9(4):e418-e430.

4 Lindblad AS, Lloyd PC, Clemons TE, Gensler GR, Ferris FL 3rd, Klein ML, Armstrong JR; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Change in area of geographic atrophy in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS report number 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009 Sep;127(9):1168-74.

5 Biarnés Marc et al. Increased fundus autofluorescence and progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: the GAIN Study Am J Ophthalmol, 160 (2015), pp. 345-353.e5

6 Tan ACS, Pilgrim MG, Fearn S, et al. Calcified nodules in retinal drusen are associated with disease progression in age-related macular degeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(466):eaat4544.